Koreatown in Los Angeles is vibrant with traditional cuisine, modern culture, and a multiethnic, strongly loyal community.

I was standing outside Le Cercle, a bar on Western Avenue in Koreatown, Los Angeles, late one night in November 2008. A stranger who I had never met before was eating a taco right next to me. He was too astonished to refuse when I asked for a bite when I was 22 and obscenely inebriated. One mouthful turned out to be insufficient, so I pulled my girlfriends across the street to the taco truck that was parked in the Sizzler parking lot. We met Roy Choi, the truck's owner, who we subsequently discovered. He was giving Los Angeles its maiden weekend tour in his brand-new Kogi BBQ truck.

Le Cercle, my twenties, eating with complete strangers, and the Sizzler are all gone now. Korean tacos, youthful exuberance, and the magic of discovery are things that will never go away in Koreatown, where change is quick, thrilling, devastating, and relentless.

In 1980, Los Angeles County officially recognized Koreatown, largely as a result of Hi Duk Lee's efforts. The neighborhood was made into a "Second Seoul" by Lee, a businessman, and civic leader, for the influx of Koreans who came to Los Angeles after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the restricted quota system based on national origin. In the 1970s, Lee established a number of companies between Olympic Boulevard and Normandie Avenue, among them VIP Palace, one of the city's first Korean restaurants. He bought blue tiles and had it constructed in a conventional architectural style. The buffet, which my parents used to attend before my siblings and I were born, became a fixture in the neighborhood. It's where Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer Prize-winning food critic who, before passing away in 2018, helped many Korean restaurateurs become wealthy, first learned about our spicy food.

Currently, Los Angeles has the greatest ethnic Korean population outside of Korea, and our neighborhood, Koreatown, is the center of the diaspora. Hangul, the Korean alphabet, is scrawled over and across every block in the area, advertising eateries and coffee shops, dry cleaners and florists, supermarkets and test-prep centers, and karaoke clubs. I was raised in the San Fernando Valley, but my family and I frequently traveled to Koreatown for food, shopping, haircuts, eye exams, and other services that were more or less exclusively offered by other Koreans. Since I was a child, my grandma has resided there; she turned 91 this year. She has never had to use English other than to converse with her grandchildren, as far as I can recall.

Despite being abandoned for many years, VIP Palace is still standing, its orange façade stenciled with images of poultry, kids, and a guy playing the accordion by the Oaxacan art collective Lapiztola. Since 2001, the location has been occupied by the family-run Oaxacan-Angeleno restaurant Guelaguetza (entrées $6–$26). It is the first authentic Mexican restaurant to obtain the coveted James Beard Foundation America's Classics honor, and one of only a few in Los Angeles. The proprietor, Bricia Lopez, told me, "A Korean building dishing up regional Mexican food is the spirit of Los Angeles." The diversity of Angelenos is what makes Los Angeles special, and K-Town is the epitome of Los Angeles.

Guelaguetza used to be a sizable, crowded indoor restaurant with a full bar, a world-class mezcal list, and live music acts before the COVID outbreak. In the place where there used to be a parking lot, there is now a patio that is airy and cheery but has a smaller capacity and no music. Guelaguetza is famous for its moles, which are rich sauces created with intricate mixtures of ingredients, many of which are imported straight from Oaxaca and include peppers, nuts, fruits, seeds, spices, and handmade chocolate. Customers are waiting up to get their taste of Oaxacan cuisine as Koreatown emerges from two years of fluctuating standards and varied levels of lockdown. Every eatery is crowded, according to Lopez. "I don't blame people for wanting to eat out."

This is good news for the businesses that survived, but for many Korean eateries, the pandemic lasted too long, aid was insufficient, and landlords were too cruel. When I finally left my home, which is less than a mile from Koreatown, more than a year later, some of my favorite restaurants, like Jun Won, Beverly Soon Tofu, and Here's Looking at You, had just vanished. Dong Il Jang and Nak Won, two-decades-old companies that made it through the 1992 Los Angeles uprising and the devastation of Koreatown, failed to survive until the year 2020.

I left my toddler at home with his father for the first time since his birth in April 2020 as soon as I had finished my vaccinations. For the tastiest pig ribs and pork neck stew this side of the Pacific, I went to Ham Ji Park (entrées $10–18), and I went to Dan Sung Sa (entrées $13–19) because, well, I was just dying to get to Dan Sung Sa. As a hangout for Korean immigrants, Caroline Cho launched the pub and restaurant in 1997. Up until COVID, it never had a single day of inactivity. We all had to suffer, but now that we are all well and back, it is the only thing that counts, she remarked. "What more could I possibly need? Not just me, either. The entire planet was involved."

The design of Dan Sung Sa was inspired by the informal eating, drinking, and relaxing spaces known as pojangmacha in Korea. The decor is traditional Korean, with a bar and an open kitchen at its center. It was created to seem like the street stalls you might find in Busan or Seoul's back alleys. The walls and wooden counters are seasoned with cordial graffiti, years of charcoal smoke, and soju spills. The parking lot was consistently packed with vehicles up until last year, each one being serviced by a valet from a Koreatown strip mall. It currently houses Dan Sung Sa's outdoor setup, a street tent built to abide by COVID regulations but more so reminiscent of the modest, comfortable pojangmacha I've visited in Korea. As I ate grilled squid and drank bowls of the milky rice wine known as makgeolli, I experienced the joyful restoration of something priceless that had almost been lost.

Los Angeles is known more for its sprawl and diversity than for the beauty of its built environment, and Koreatown epitomizes this eclectic "everythingness" in a way that makes me proud to be a resident. Koreatown has a jumble of architectural styles and a lot of strip malls. The merging of so many histories into a congested metropolitan scene here makes it obvious that the past always resides inside the present.

You may find meticulously preserved landmarks like the Gaylord Apartments (built-in 1924) and the lovely Art Deco Wiltern Theatre along the 112-mile-long Koreatown section of Wilshire Boulevard, which serves as the neighborhood's commercial spine (1931). The oldest Jewish community in Los Angeles is located at the Wilshire Boulevard Temple (1929), which just underwent an extremely costly enlargement. In 2015, longtime temple supporter Audrey Irmas raised money for the Audrey Irmas Pavilion by selling a Cy Twombly painting at auction for more than $70 million. The pavilion was created by Rem Koolhaas and OMA colleague Shohei Shigematsu. Since the building's opening in September, Wilshire's skyline has been altered. In contrast to the Byzantine Revival temple, it is a large, striking construction that is flashy and contemporary.

While Koreatown has become significantly more Korean since the temple was constructed, despite its name, it is much more than just an ethnic neighborhood. With almost 120,000 people living within its 2.7 square miles, it is both one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the nation and the most crowded in Los Angeles County. With two-thirds of its citizens being foreign-born, the population is extremely diversified, with around half of its residents being Latino and a third being Asian. The diverse cultural amalgamation is what gives Koreatown its unique vibrancy. I recall, for instance, watching the Korea-Mexico World Cup match in 2018 at Biergarten (entrées $19-$28), a gastropub on Western Avenue that serves pork schnitzel and kalbi (short-rib) nachos, with a packed house of hyphenated American fans cheering for both teams and downing beer at eight in the morning.

In Koreatown, all the promises—and disappointments—of the metropolis are magnified. The social fabric of Los Angeles is intricately knit here. I recently had dinner in Chapman Plaza, a 1920s shopping district with an elaborate Spanish Revival facade and a vibrant, distinctly K-Town bar and restaurant culture. I had dinner at one of my favorite Korean BBQ restaurants, Quarters (entrées $12–$48), where you can order draught IPAs to go with your short ribs and dunk fiery pork belly and pork jowl in a fantastically original dish of melted cheese. Starting around 7 o'clock, the music is played at a nightclub volume.

The parking lot, which was formerly the town's hottest late-night valet scene, has been transformed into a full-fledged pojangmacha village, complete with large tents, meat and alcohol, and an exhilarating festival atmosphere. The HMS Bounty is a historic pub on the first level of the Gaylord Apartments that has been open since 1962. According to my father, it was one of only three venues in Koreatown where white people could be seen in his day (the other two being El Cholo and Taylor's Steakhouse). It has a nautical theme and is as worn-in and cozy as an old favorite hoodie. Before Koreatown existed, in the 1960s, Ramon Castaneda, the current owner, began working there as a teenager. The Bounty, however, remains unchanged even though the neighborhood has altered.

Gimlets and Manhattans were consumed for hours by my buddies and me before moving on to the Prince. I once recorded my segment in one of the Prince's back rooms as an unnamed talking head for Anthony Bourdain's Koreatown episode of The Layover. It was then a fried chicken and soju establishment with a middle-aged Korean clientele. It now draws a varied, young crowd and gets busy even on weeknights. My go-to yogurt soju at the Prince was not available when I attempted to order it. Instead, I ordered a dirty martini.

If we had been younger, we might have stayed out later after we closed the bar. In Koreatown, you may find 24-hour eateries like Sun Nong Dan (entrées $16-$80) and Hodori (1001 S. Vermont Ave.; 213-383-3554; entrées $12-$36) that are both wonderful and still great. There are typically one or two locations where you may purchase secret soju after hours if you inquire around.

After midnight, as we were making our way back to our car, we came across a homeless man defecating on the pavement. We did our best to give him some space. It was a stark reminder that there is a housing crisis in Los Angeles. In Koreatown, where residents prevented the construction of a shelter months before COVID, the impacts are evident. According to Jessica Sykes of the Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance, a multiethnic workers' rights organization and community group, "pre-pandemic, a third of Koreatown households were earning under $25,000 a year."

"The pandemic has made those who were already vulnerable very conspicuous and even more vulnerable." L.A. is the city of sunlight and noir, of aspirations, realized and crushed to dust, according to city historian Mike Davis. L.A.'s core is in Koreatown. Each night, on any street, you can discover both magic and misery.

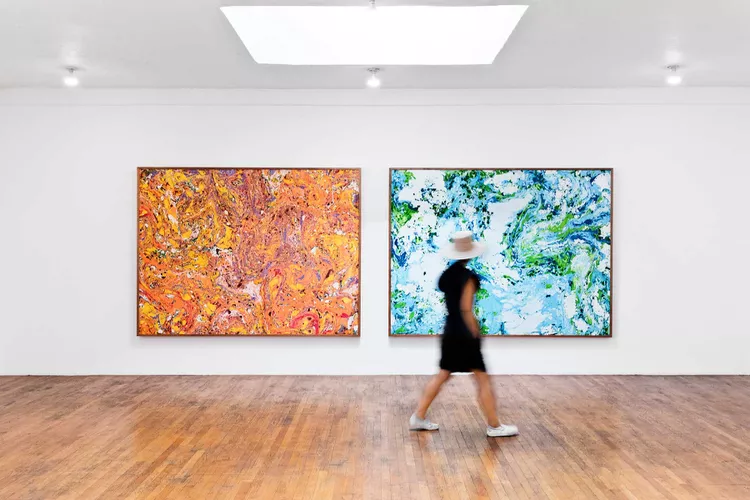

On the second floor of a dilapidated brick-and-stucco structure on Seventh Street is a modern gallery that was created and is managed by artists. The founder Young Chung gave the gallery its name after the site of his one-bedroom flat, where he presented the first exhibitions in 2010. Chung discovered this more permanent display space above the first Spanish-language Alcoholics Anonymous in Los Angeles after his landlord caught on and closed him down. Naturally—and there's something very K-Town about this—Amigos Liquor is right around the corner, and the most well-known tenant of the building is OB Bear, a legendary Korean bar that is currently shuttered after a significant fire in November 2020. The OB Bear fire had no impact on Commonwealth & Council, however, the area had previously burnt. When Chung and codirector Kibum Kim took over, they discovered burned-out walls concealed by a cinder block. They collaborated with friends to reconstruct the walls while absorbing and altering the damage.

The gallery serves as a gathering place for a variety of established and up-and-coming artists, art buyers, and other culturally interested Angelenos. I attended a solo exhibition by Colombian artist Carolina Caycedo, who was born in London and is currently residing in Los Angeles, and I overheard two men being given an informal tour by a gallery buddy. After a year of pandemic constraints and the restrictions of becoming a new father, I marveled at this effortless familiarity and this delightful friendship when another gallerist stopped by while I was there, presumably wanting to hang out. Kim explained to me, "We don't hold ourselves up as some sort of community leaders, but we are very much part of the greater fabric of the area. "We've worked with a seamstress who is right next door. Our neighbors are people we know."

I've only ever encountered a certain type of coffee shop in Korea and Koreatown. The Yellow House Café on Oxford Avenue, a vintage colonial single-family home that underwent transformation alongside the neighborhood instead of being demolished, is my favorite local example. It's a sweet spot with a sizable patio in the backyard and a beautiful aesthetic—string lights, rounded typefaces, and an earnestly upbeat ambiance. You may get whimsical, flowery cocktails like a sweet-potato latte or an Almond Roca cappuccino, but the coffee and tea aren't artisanal. The menu is extensive and features a variety of pasta dishes in addition to a number of comforting Korean cuisine (some carb-focused Korean-Italian fusion is another common element of the Korean café). Red-bean shaved ice and many waffle varieties are included in a large list of sweets. It's a lovely location with a strong, native-born attitude.

The past few years have seen the emergence of a new type of coffee shop—specialty establishments serving expertly roasted craft coffee and sporting gentrifier-chic storefronts that cause people like me to slow down and wonder, "Oh, what's this place?" Spl. Coffee, located five blocks to the east, feels distinctly domestic, even if the Yellow House could have been plucked from Korea. American second-generation owners Karen Lee and Jonathan Dizon are from Silver Lake and Echo Park, respectively. When the chance to open a coffee shop presented itself, Lee and Dizon relocated to a strip mall on a sparsely populated section of Third Street.

Either everything at Spl. is created on-site, or it is purchased from local suppliers. On my most recent visit, I enjoyed a cappuccino while taking in the atmosphere, which is bright and airy with minimal decoration aside from an electric-blue mural of chubby chickens and a cat sipping coffee against an L.A. skyline. This was painted by Cache and Atlas, two graffiti artists from nearby Alhambra and Guatemala City, respectively, whose colorful chickens and cats adorn walls throughout the city.

I asked Lee, who has worked in the food and beverage sector her entire career, why she was drawn to coffee in particular when she stopped by my table for a chat. She said, "It brings people together." In the last two years, the world has changed, but this community remains. Koreatown is tough, has weathered fires and plagues, and is a place where happiness can be found after grief.