One travel writer decides to go in search of these evasive large cats and then writes a report about the fragile peace that exists between them and their human neighbors.

Our tour guide, Chewing Nobu, yelled at us to "Get in the car right away" just as his staff was beginning to set up a tailgate lunch. "Get in the car right away!" It took less than a minute for our gear to be loaded, the hot tea to be poured out with reluctance, and the car doors to be closed after he came rushing down the mountain with a cloud of dust in his wake. After that, we started hurtling downward at an extremely rapid pace.

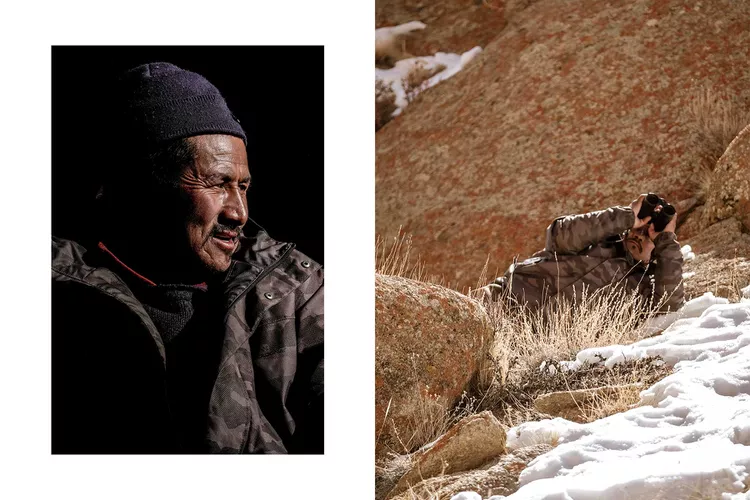

It did not appear to be relevant that the road, or something that may pass for a road, was located next to a steep cliff. When we were getting close to a bend in the road that went around a blind corner, Nobu yelled at the driver to slow down. “Stop!” After he jumped out, he sprinted forward while focusing his binoculars on a ridge in the distance. When he turned back to our vehicle, he did so with a broad smile plastered across his face.

The village of Alley, located in western Latah, India's northernmost province, is one of the very few accessible regions where visitors stand a decent chance of spotting this evasive and endangered big cat. We had been searching for the snow leopard there and in the surrounding area for nearly a week when we finally found it. Following footsteps, we had hiked up slopes of loose shale, lurked in wait along grassy hills, and battled winds that looked far colder than the reading on our weather apps that said it "felt like." We had observed two different species of wild sheep, an ibex, Himalayan wolves, a variety of bird species, and a single red fox during our trip. However, the snow leopard, also known as the "grey ghost" in the area, managed to evade our search. To this point.

"Take a look in that direction," Norbury instructed, pointing to the peak of a hill that was approximately a half a mile distant. The response I gave was, "I don't see anything." As if in response, a snow leopard materialised before them, stretching in the traditional "cat pose" yoga position, brushing off the dirt and chill of the previous night so that she might bathe in the warmth of the early morning sun. Even from afar, I could tell that she was stunningly beautiful. Her fur was a greyish beige colour, and the rosette marks on it were dark against the lighter backdrop. She was currently giving her coat a nice lick. Her broad and lengthy tail, which she flipped every once in a while, was characteristic of her.

She had three cubs with her, one of which was trying to engage its siblings in a game, but they were stubborn and wouldn't move. The mother dipped her head and made room for her child to clamber atop her back before letting the child down again. She abruptly halted what she was doing, sat herself up, and turned in our direction. A cloud of dust that could be seen for miles around had been left behind by the excited safari-goers and other residents of the Snow Leopard Lodge, which Nobu owns and operates as a homestay. Word of the sighting had spread, and anxious visitors and other residents had arrived. (February is smack dab in the heart of the busiest travel month, so it was to be expected that there would be some company, even though in this relatively isolated region, it does not often feel like a throng.)

However, it appeared that the mother was paying attention to all of the human activities going on around her. We were cautioned to keep the noise level down lest she get up and depart. She kept an eye on us while perched on her haunches. As a flock of chukar partridges fluttered in a tree below me, the wind with a "feels like" temperature of -10 degrees Celsius made its way through my thermals. There was no sign of alarm among the wild sheep grazing on the slope above. After much deliberation, Lady Leopard ultimately concluded that there was no longer any need to be concerned about our safety and went to sleep. We all let out a sigh of relief at the same time.

"I told you that you wouldn't go without seeing the shan," Norbu stated with a smile, utilizing the Ladakhi word for snow leopard. "I told you that you wouldn't leave without seeing the shan." I smiled back at him. The majority of western Ladakh is devoid of vegetation, and its mountains are bare and coated in shale. Finding a snow leopard, or any animal for that matter, is like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. There are so many other animals out there. However, Norbu, who has been leading tourists since 2004, has become something of a legend in the field of detecting these species. Photographers, directors of documentary films, and environmentalists all look forward to working with him. While we were camping in the rear of the Snow Leopard Lodge and searching the nearby hill for indications of the animal, he made the statement one day, "To me the shan is like the Dalai Lama of nature," which he made while scanning the hill for traces of the animal. "It is by far the strongest beast in this area. Don't we tend to look up to those in positions of authority?

There was a time when the connection between man and apex predator was not as respectful as it is now. Norbu recounted that his grandfather and father, both skilled hunters, taught him how to track snow leopards when he was a boy. His grandfather and father would seek vengeance on snow leopards when the cats killed their cattle. (In the past, snow leopards were also murdered for their fur and various portions of their bodies, which were employed in alternative forms of medicine.)

In 2002, the Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust (SLC-IT), a highly regarded organisation that operates in the Himalayan regions of Ladakh and Spiti, gave a boost to the conservation of the species in Ladakh by introducing homestays in regions where human-animal conflict was an ongoing issue. These regions were located in areas where homestays were established in areas where there was a persistent problem. According to Dr. Tsewang Namgail, head of the SLC-IT, "the homestays are the single most essential contribution to conservation." Before they arrived, travellers who went on hikes or safaris typically camped in the open air. They were notorious for not taking their trash with them. People in the neighbourhood voiced their opinion that if tourists stayed with them, it would be beneficial for both the economy and the environment.

In those days, just a small fraction of the money that tourists spent actually made its way back into the economy. In the western region of Latah, the SLC-IT has provided assistance to locals in the establishment of more than 200 homestays, including the Snow Leopard Lodge, as well as provided training to locals for careers as trekking guides and naturalists. Along with his family and few other people, Nobu manages the resort. Although the accommodations are not particularly luxurious (all of the rooms have wood-burning stoves for heat, and guests must fetch their own buckets of hot water), the staff is quite kind and helpful. It is also without a doubt the finest example of its kind that the area has to offer.

In addition to the homestays, Mamgai tells me that village cafés that sell handcrafted souvenirs and a livestock insurance programmed that covers attacks by predators have helped reduce the amount of human-animal conflict even further. Both of these initiatives are promoted by the SLC-IT, but are run independently by the villagers. Since the homestays got underway, there has been an absolute cessation in the number of vengeance killings. Norbu explained that many had come to the conclusion that they might earn more money by preserving the shan. Although estimates put the number of snow leopards living across the Himalayas at between 400 and 700, Namgail claimed camera traps suggest a far greater number.

On the day that was to be my last in Alley, I observed the mother bear and her cubs as they slept, played, and groomed each other for more than four hours. Norbu was the one who taught me some interesting facts about snow leopards, such as how, when they kill a large animal like a sheep, they will feed on it for a week, starting from the outer limbs and working their way all the way to the internal organs. This helps slow down the decay of the carcass and prevents it from attracting scavengers.

Norbury called my attention to the fact that it was time to depart just as the sun disappeared below the mountains. It would take me two hours to drive to the capital city of Leh, and I needed to get to the airport right away. I was tempted to stay there for a longer period of time so that I could make the most of this unique opportunity. However, when I looked through the scope to see what the mischievous youngster was up to, it was nowhere to be found. The mother was not present either. At least for the time being, the ghosts were nowhere to be found.